The head is the key part of the body, responsible for our character, our person. In contrast to the approximately 300 other bones of the skeleton, which change in size and composition throughout our lives, the head remains relatively unchanged. It is the source of our individuality. We talk, see and hear with the head, our emotional life and our balance, our locating system and our perception of the here and now are located in the head.

//Der Kopf ist das Körperteil schlechthin, dasjenige, welches unseren Charakter, unser Wesen ausmacht. Im Gegensatz zu den etwa 300 übrigen Knochen des Skeletts, die sich lebenslang in ihrer Beschaffenheit und Größe ändern, bleibt der Kopf zeitlebens relativ unverändert. Er macht daher unser Ich aus. Wir reden, sehen und hören mit dem Kopf, unser Gefühlsleben und unser Gleichgewicht, unser Ortungssystem und unsere Wahrnehmung des Hier und Jetzt sind im Kopf verortet.

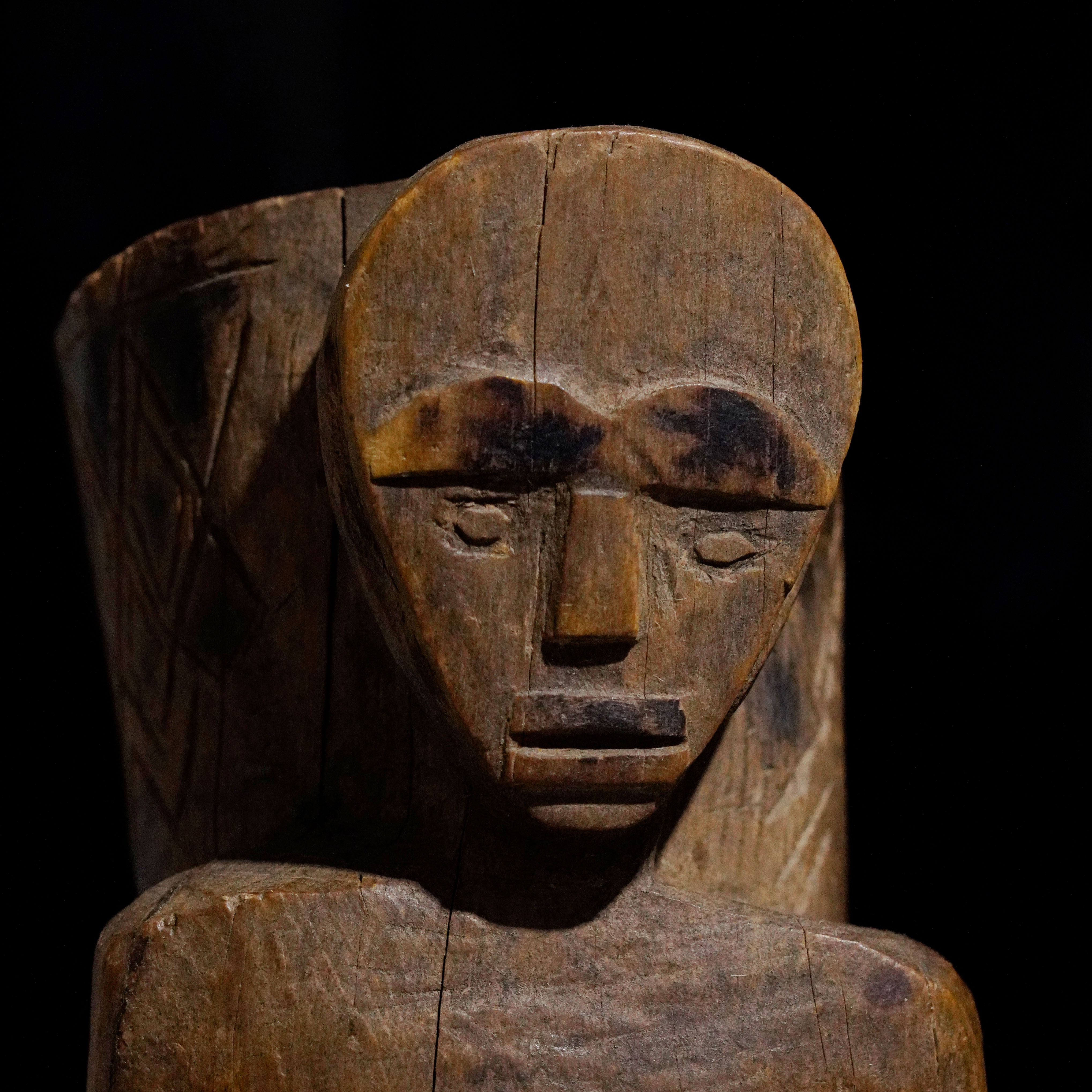

Borneo

The human head has a specific focus. As in all primates, the eyes are directed forward, and the cranium protecting the brain is greatly enlarged in relation to the facial skull and also protrudes beyond it at the front of the head, so that an altogether round head is formed without a protruding snout, but with a relatively flat, forward-facing face. Therefore, the human head, in contrast to the head of non-human animals, is often regarded in many cultures as synonymous with the sun or other celestial bodies. In addition, hair and beard continue to grow for a few days after death and the head has therefore been attributed with a life of its own since time immemorial. The cutting off of the hair is often equated with complete loss of strength and character, as the story of Samson clearly shows. In culture-specific perception, the head is often seen as a part which is representative of the whole person. This is made evident by numerous idioms such as „per capita“, „the best brains“ etc. In human representations, through all periods and cultures the head very often plays a disproportionately important role. It is either emphasized or abstracted. The representation of the head or face can be more or less taboo in many cultures, as it awakens spirits and brings the image to life by „looking back“. In the earliest depictions of human beings, the head is often missing or reduced to a line representation – quite the opposite of the often precisely depicted features of animals or other parts of the body. Children usually begin to depict humans as cephalopods without a torso or with a line to represent it. Only later do the hands become the next feature determining the figure as human.

//Dem menschlichen Kopf ist eine spezifische Fokussierung eigen. Die Augen sind wie bei allen Primaten nach vorn ausgerichtet, und die das Gehirn schützende Schädeldecke ist gegenüber dem Gesichtsschädel stark vergrößert und überragt diesen auch auf der Vorderseite des Kopfes, so dass ein insgesamt runder Kopf ohne hervorstehende Schnauze, sondern mit einem relativ flachen, nach vorn weisenden Gesicht gebildet wird. Daher wird der menschliche Kopf, im Gegensatz zum Kopf nichtmenschlicher Tiere, in vielen Kulturen oft mit der Sonne oder anderen Himmelskörpern synonym gesehen. Hinzu kommt, dass Haupt- und Barthaare sogar noch einige Tage nach dem Tode weiterwachsen und dem Kopf auch daher seit alters her ein Eigenleben zugeschrieben wird. Das Abschneiden des Haupthaares wird oft mit vollständigem Verlust der Kraft und des Charakters gleichgesetzt, wie die Geschichte von Simson anschaulich zeigt. In der kulturspezifischen Wahrnehmung wird der Kopf häufig als stellvertretendes Teil des gesamten Menschen angesehen. Das zeigen zahlreiche Redewendungen wie z.B. „Pro-Kopf-“, „die besten Köpfe“ etc.. Bei menschlichen Darstellungen in allen Zeiten und Kulturen spielt der Kopf meist eine überproportional wichtige Rolle. Er wird entweder besonders betont oder aber abstrahiert. Die Darstellung des Kopfes oder des Gesichtes kann in vielen Kulturen mehr oder weniger stark tabuisiert sein, da sie Geister erweckt und das Bild durch das „Zurückschauen“ zum Leben erweckt. Bei frühesten Menschendarstellungen fehlt der Kopf häufig oder ist auf einen Strich reduziert – ganz im Gegenteil zu den oft präzise dargestellten Merkmalen von Tieren oder anderen Körperteilen. Kinder beginnen den Menschen gewöhnlich als Kopffüßler ohne Rumpf oder mit einem Strich als Rumpf darzustellen, erst später kommen die Hände als nächstes wesensbestimmendes Merkmal hinzu.

Formosa

Since the head defines the personality and makes it possible to assign it a name, in almost all cultures it is treated with special regard, be it in representations, in burials (ossicles or skull houses), but also in the interaction with the environment, which in relation to human nature is usually not only of a peaceful kind. The fact that, almost everywhere, masks perform an enormous role in all forms of artistic expression is further evidence of this, as too the psychological phenomenon, that virtually every object with two horizontal fixed points – the „eyes“ – is automatically perceived as a face.

//Weil der Kopf die Persönlichkeit definiert und benennbar macht, wird er in fast allen Kulturen in besonderer Weise gewürdigt, sei es bei Darstellungen, bei Bestattungen (Bein- bzw. Schädelhäuser), aber auch bei der Auseinandersetzung mit der Umwelt, die der menschlichen Natur gemäß meist nicht nur friedvoll erfolgt. Der Umstand, dass Masken fast überall einen immens großen Teil aller künstlerischen Äußerungsformen darstellen, deutet darauf hin, ebenso wie das psychologische Phänomen, dass quasi jedes Objekt mit zwei horizontalen Fixpunkten – den „Augen“ – automatisch als Gesicht empfunden wird.

Naga-Land, Sulawesi, Northern Philippines and Nias

The skull cult of the European Celts is perhaps the most prominent manifestation of the head cult, alongside the „head hunting“ thematised in the current IFICAH exhibition. In many respects comparable to the cults in South East Asia, it illustrates that we humans have the same traits everywhere. The head apparently stands as pars pro toto for the entire material and spiritual personality, in „old Europe“ as in Asia. Greek historians (e.g. Diodorus) made records about the Celts as early as the 1st century B.C.: „They embalm the heads of their noblest enemies and keep them carefully in a chest, and when they then show it to guests, they boast that neither their ancestors nor their father or even they themselves would have parted with this head, even for a great deal of money. In Celtic burial rites the head and body were apparently treated separately. In ritual places, stelae or stylized trees were erected with cut-off real heads or ones carved from stone placed on them, as for example in Roquepertuse or Entremont (France). The close similarity to Borneo, Sulawesi or Luzon is very obvious in all this. Smoothed and pierced skull fragments are often found during excavations as amulets amidst house remains, and this from the Neolithic Age until a few decades ago. And even today we all know the „skal“ of the Swedes, a toast that is still reminiscent of the skull cup for ritual drinking – a word that has the same stem as skull.

//Der Schädelkult der europäischen Kelten ist neben der in der aktuellen IFICAH-Ausstellung thematisierten „Kopfjagd“ vielleicht die prominenteste Ausprägung des Kopfkultes. In vielen Belangen vergleichbar mit den Kulten in Südostasien, zeigt er, dass wir Menschen überall gleich geartet sind. Der Kopf steht offenbar als pars pro toto für die gesamte materielle und spirituelle Persönlichkeit, im „alten Europa“ ähnmlich wie in Asien. Griechische Geschichtsschreiber (z.B. Diodorus) berichten schon im 1. Jahrhundert v. Chr. von den Kelten: „Die Köpfe ihrer vornehmsten Feinde balsamieren sie ein und verwahren sie sorgfältig in einer Truhe, und wenn sie diese dann den Gästen zeigen, so rühmen sie sich, wie einer ihrer Vorfahren oder ihr Vater oder auch sie selbst diesen Kopf um vieles Geld nicht hergegeben hätten.“ Bei keltischen Bestattungsritualen wurden Kopf und Körper offenbar getrennt behandelt. An kultischen Orten waren Stelen oder stilisierte Bäume mit echten oder aus Stein gehauenen abgetrennten Köpfen aufgestellt, wie z.B. in Roquepertuse oder Entremont (Frankreich). Die Nähe zu Borneo, Sulawesi oder Luzon ist bei alledem sehr augenscheinlich. Geglättete und durchbohrte Schädelfragmente werden bei Ausgrabungen als Amulette häufig inmitten von Hausüberresten gefunden, und zwar von der Jungsteinzeit bis noch vor wenigen Jahrzehnten. Und bis heute kennen wir alle das „skal“ der Schweden, ein Trinkspruch, der noch an den Schädelbecher für rituelle Trinkgelage, erinnert. Oder eben an die Schale – ein Wort, das denselben Stamm wie skull (engl. Schädel) hat.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar